For all the disruption that affected English football during the war, the Italian game emerged relatively unscathed. Admittedly, the national team missed out on the chance to defend their crown at the “missing” World Cups of 1942 and 1946, and for two seasons the national league championship was cancelled, but it was a far cry from the near total club blackout that impacted the British Isles.

Arguably the greatest beneficiaries of this continuity were Torino. The club won Serie A in the 1942-3 season, before Italy’s involvement in the war finally put an end to the national football league for two seasons. When the league was re-established in 1945-6 they were again triumphant. The next few years would herald unrivalled dominance.

Italian football had in the 1930s proved itself to be the match of any country in the world. The arrival of the Oriundi combined with a burgeoning domestic game made Italy the envy of Europe. At a club level Juventus had proved themselves supreme in the early 1930s, as well as supplying the backbone for Italy’s 1934 World Cup winning team. By the time that the 1938 World Cup came along, Bologna and Ambosiana-Inter had brushed aside the Old Lady and taken on the mantle of Italy’s leading sides. As Italy entered the 1940s Torino were ready to reign.

The side that Torino built was not based on a revolutionary tactic or formation. It was not based on the acquisition of a band of foreign mercenaries. Instead it was based on the skill and work ethic of a group of men drawn remarkably close by the external events impacting Italy at the time.

|

| Valentino Mazzola |

The focal point of La Grande Torino and the man with whom the team will forever be most closely associated was Valentino Mazzola. A sublimely talented inside-forward he was capable of moments of true genius. Unrivalled for skill within contemporary Italy he possessed a rare balance allied with a range of passing that allowed him to find his teammates with unnerving accuracy. Perhaps his greatest quality though was his leadership. Mazzola was a man that others wished to follow, and the aura that surrounded him inspired loyalty and confidence in the rest of the team.

The partnership that Mazzola struck up with fellow inside-forward Ezio Loik was the team’s greatest strength. The two of them were a constant threat to defences and both were more than capable of scoring goals as well as creating them. The man who most frequently benefitted from the passes of Loik and Mazzola was striker Guglielmo Gabetto. Gabetto had begun his career with Juventus before moving across the city to Torino where he established himself as a prolific goalscorer for both club and country.

|

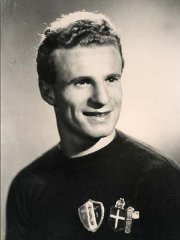

| Ezio Loik |

Yet this was a team with quality throughout. When Italy beat Hungary in May 1947, an incredible 10 of the starting 11 were drawn from Torino. Never before (or since) had a single club provided such a concentration of stars for the Azzurri. When teams faced Torino they were often beaten before they started as they were simply in awe of the range of options I Granata possessed. In the instances where the opposition put up a fight, Torino almost invariably wore them down through their superior fitness, frequently grabbing games at the death.

The remarkable thing about Torino’s dominance was not just the consistency with which they beat opponents, but their margin in doing so. The team played with freedom and passion, and revelled in scoring goals. Almost 500 scored across their five title winning seasons was testament to that. Defensively too they were outstanding, and the completeness of their victories only served to underline the disparity between Torino and their opponents.

In May of 1949 Torino travelled to Lisbon for a friendly with Benfica, a testimonial for Xico Ferreira. Benfica ended as victors in a pulsating 4-3 game, but the result of the match would soon pale into insignificance. On the return flight from Portugal the plane carrying the Torino squad crashed into the hillside at Superga, a town near Turin, killing all 31 passengers.

What followed was a period of national mourning as fans of the club struggled to come to terms with the disaster. The Torino team had embodied the vigour and vitality of youth. The way that they brushed aside their opponents made them appear to be supermen, invincible, yet the tragedy only proved that mortality is universal.

|

| The wreckage following the crash |

Over half a million mourners packed the streets on the day of the funerals, while the ceremonies received live coverage on the radio. Even in a country where the scars of war were still fresh, the emotional impact of the disaster could not be overstated. The attachment of the masses to La Grande Torino ran deep and to this day fans still make a pilgrimage to Superga each year to remember the team.

In respect of Italian football in general and Torino in particular the crash had a profound impact. Many feel looking back that with the Torino players participating Italy would surely have stretched their run of World Cup victories to three. Yet the form displayed by the Italians prior to the disaster did not hint at certain victory. In particular a 4-0 defeat at the hands of England in Turin threw doubts on the calibre of this vintage. Certainly the Azzurri would have been stronger in 1950, where they lost to Sweden and beat Paraguay en route to a first round exit, had the likes of Mazzola and Loik been available.

The impact on Torino was much longer lasting. The club did not win Lo Scudetto again until 1976 and have lived almost continuously in the shadow of neighbours Juventus. Indeed despite high points such as victories in the Coppa Italia and a narrow loss in the 1992 UEFA Cup final the team have never again hit the heights that their famous predecessors enjoyed.

For the club then it would almost be natural to view the disaster in pure footballing terms, to see what might have been, had the tragedy not taken place. The esteem in which the players were viewed though makes that impossible. The affection that pervaded the city of Turin for the lost players meant that it would always be a human tragedy, rather than just a sporting one. Furthermore the enduring memory of their greatness was why Italian journalist Giovanni Arpino could confidently say “That Torino team never died.”

1 comment:

Great blog. Really enjoy it.

Post a Comment