After Italy’s victory in the 1934 World Cup a match with England provided an opportunity to determine the unofficial “world champions”. Recent form for England had not made them obvious candidates for such a title (they had lost 2-1 against both Hungary and Czechoslovakia in the May of 1934), but their position as the game’s inventors served to provide the necessary prestige for the match. Furthermore England had managed a 1-1 draw in Rome in 1933 and so remained one of the few top European sides that the Italians had never defeated. Victory in this game would give even greater validity to their claims as the best in the world.

The match also provided a chance for Vittorio Pozzo to prove himself in England. Pozzo was a tremendous anglophile who had spent a number of his formative years in the North of England and had come to gain a real passion for the English game. While in England he developed a deep admiration for Manchester United and in particular their attacking centre-half Charlie Roberts. Roberts was instrumental in the formation of the Professional Footballers Association, to the detriment of his international career, but he was most notable for his ability to start attacks from deep positions in the United midfield. When Pozzo became a manager a Roberts-esque centre-half was mandatory for any of his teams.

|

| Vittorio Pozzo (left) |

The other Englishman that inspired Pozzo was Herbert Chapman. Along with Hugo Meisl the trio formed a lasting friendship, built on a mutual respect and love for the game. Although Chapman had died in the January of 1934 the match against England at Highbury (the home of Chapman’s Arsenal) was a fitting place for Pozzo to attempt to conquer the English game. What’s more, Arsenal provided an unprecedented seven players for the match against Italy, while Tom Whittaker of Arsenal acted as trainer (the England team was still selected by committee at this stage).

Prior to the game the Daily Mirror (rather implausibly) suggested that a “ten goal victory must be our aim”. Against a team as strong as Italy that was always a pipedream yet they suggested “if we could beat the Italians by ten goals and on the day deserve such a margin, the stock of England, not just English football, would jump as it has not jumped for years”. Whether this was anti-Fascist sentiment (the game took place four years before an England side gave the Nazi salute before a game in Germany) or not is unclear, but it was never likely to come to pass.

What did take place was a game as fiercely contested as any in the pre-war era. Before the match the England side had been referred to as (Ted) “Drake’s armada” in anticipation of the ferocious way they would challenge the Italians. It was no hyperbole for the press afterwards to dub this match “The Battle of Highbury” given the intensity with which the two teams fought for victory.

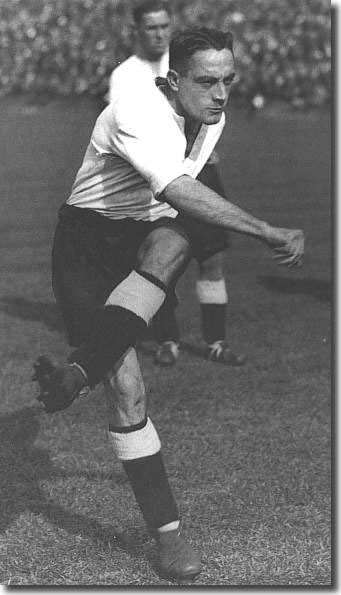

|

| Ted Drake |

The game started at a remarkable pace, with enough controversy and action to fill a handful of games in the first fifteen minutes. Within a minute Ted Drake had been put clean through on goal, only to be hauled down in the area before he could shoot by Italian keeper Carlo Ceresoli. Up stepped Eric Brook, but Ceresoli made a miraculous save to turn his shot over the bar. Seconds later the first major injury was suffered. As Luis Monti went to clear the ball Drake blocked his kick, forcing the Italian from the field with broken bones in his foot.

Shortly after, England’s sustained pressure was brought to bear. Another foul led to a free-kick for England to be taken by Cliff Britton. His whipped delivery was headed in by Eric Brook to make amends for his missed penalty. Five minutes later and Brook scored again. This time he took a free-kick from the age of the area and blasted it past the diving Ceresoli. Had he not missed the penalty he’d have had a hat-trick within ten minutes. England though did not have to wait long for more goals. Drake scored a header after 15 minutes to put the home team in a commanding position.

As the half progressed it became more and more violent. Wilf Copping was noted as the hardest player of his day and was not a man to shy away from a confrontation. Copping once observed that it was “easier to play against ten men than eleven, even easier against nine”. As the Italians sought revenge for the injury to Monti they soon found that Copping was unlikely to be a pliant victim.

Ted Drake was soon off the pitch following a series of brutal challenges. Such was the use of studs from the Italian players and the height of their “tackles” that they had managed to rip through his socks and split open his leg! Italy’s half-backs resumed their assault in retribution for Monti’s injury as Luigi Bertolini elbowed Eddie Hapgood in the face off the ball and broke his nose.

|

| Wilf Copping |

Monti’s return to the pitch after his injury was brief. Stanley Matthews later remembered “Just before half-time, Wilf Copping hit the Italian captain Monti with a tackle that he seemed to launch from somewhere just north of Leeds. Monti went up in the air like a rocket and down like a bag of hammers and had to leave the field with a splintered bone in his foot.” At half-time Copping asked the England team doctor “How’s that Eytie?”, “Oh! He won’t come back!” was the response. “Bloody good job! He’d soon be back in the dressing room” Copping replied.

In the second-half the Italians were able to stage a brief come back. Giuseppe Meazza scored two and hit the woodwork. The Italians were denied repeatedly by Frank Moss, the England goalkeeper. England though clung on to record a memorable victory over the world champions, albeit in regrettable circumstances.

After the game the Daily Mirror set out the injuries suffered by the England players: “Hapgood – broken nose; Brook – arm x-rayed; Bowden – injured ankle; Drake – leg cut; Barker – hand bandaged; Copping – bandaged from thigh to knee.” One newspaper reflected the level of violence in their byline: “By our war correspondent”.

No comments:

Post a Comment